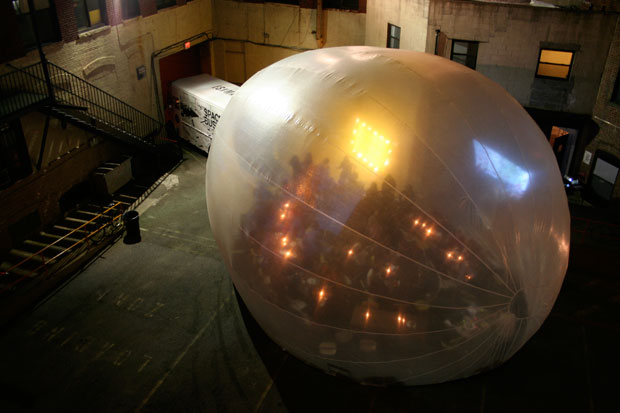

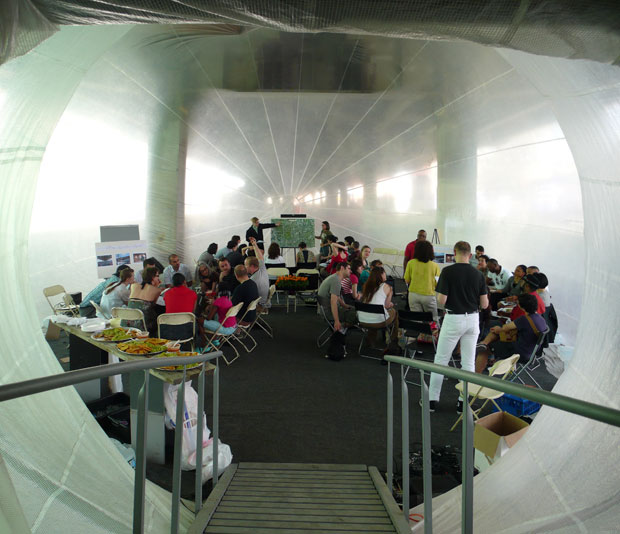

The Spacebuster is build on the basis of a step van and a big inflatable space coming out of the back of the van fitting up to 80 persons in it. People enter the bubble through the passenger’s door of the van walking through to the back down a ramp right into the inflated space. The bubble is supported by air pressure generated by a fan underneath the ramp. The membrane of the bubble is translucent so people on the inside can see schematically what´s going on outside and vice versa. So the membrane acts as a semi permeable border between the public and the more private.

Foto: (c) Alan Tansey

This way the surroundings become the backdrop of the scene as viewed from the inside and the Spacebuster a stage in terms of a public theater piece. Projections onto the membrane can be viewed from the outside as well as from the inside of the space. Depending on the program taking place in the Spacebuster the space is furnished with desks, chairs, dinner tables in different layouts. As the flexible structure of the bubble can adjust to the surrounding it squeezes underneath a bridge, wraps around a tree or casts the pattern of a fence or the profile of a façade.

Traveling through Manhattan and Brooklyn on 9 consecutive evenings the Spacebuster hosted various events that emerged from cooperations of raumlaborberlin, the Storefront for Arts and Architecture and different local art institutions, nonprofit organizations and communities. The mixing of more formal formats as workshops, lectures, screenings etc. with everyday easily accessible program as dinners, bar gathering and parties created a special atmosphere to the space as well as the momentum of the visibility of the things happening to the public. For instance there were workshops about the development of a public area held within the Spacebuster on the spot where the further development was supposed to take place. Thus the questions discussed and the developments projected were catalyzed by the pathos of the real.

As a research tool the Spacebuster disclosed the peoples relation to the urban space as well as a quite big amount of invisible borders within the city that shape the built and the social space.

Spacebusting

by Gideon Fink Shapiro, NYC, April 2009

From within a hard shell swells the soft bubble, a billowing urban room hatched in the back of a delivery van. This genie in a lamp makes for instant theater, and shows how wind in a bag can make instant architecture. But this is no ordinary pop-up circus tent. Rather than being consumed as entertainment, like a circus act or the dead matter of architecture, Spacebuster consumes its viewers, and they in turn transform it. Touch it, see and be seen through it, drink and debate inside it.

New York is full of invisible walls. The spaces that Spacebuster busts are penned by intangible limits. Space busting is about uncompressing the void, sprouting between the cracks, squeezing the vacuum, enveloping the moment. Ambiguity no longer equates to amnesia. The strange yet banal spectacle of inflation, the making of walls and boundaries, turns out to be an overture to cross those boundaries and infiltrate the volume. Spacebuster mobilizes us to mobilize space.

Enter Spacebuster, the amorphous enigma: A certified building by the Department of Buildings. A licensed vehicle by the Department of Motor Vehicles. A certified street event by the Department of Transportation. An experimental realm-laboratory by Raumlaborberlin. Inhaling inert space, it holds its breath until the space reawakens, if only for a moment. Will the memory last? How will we convert this experience of agile placemaking into everyday practices of urban space busting?

Program

1 Thursday 16 April, 6 pm

softopening and press preview

2 Friday 17 April, 6.30pm

Public Vernissage at Gansevoort Plaza with storyfront-sandwiches and talks by raumlaborberlin

3 Sunday 19 April, 7pm

Dinner and party with raumlabor in the Spacebuster in The Courtyard of The Old American Can Factory, 232 Third Street at Third Ave., Gowanus Brooklyn, hosted by The Eighteenth, a roving restaurant run by artist Anne Apparu. Organized in conjunction with MeanRed Productions and XØ Projects.

4 Tuesday 21 April, 7.00pm

Presented in conjunction with Goethe Institute New York

Gathering at Wyoming Building, the new events space of the Goethe Institute NY followed by a lecture by Raumlabor and presentation of the Fragmental Museum at Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural Center

5 Wednesday 22 April, 7.00pm

Screening and discussion: „Examined Life„, organized in conjunction with Gavin Browning/Studio-X/Columbia GSAPP

Followed by open discussion with Astra Taylor, Avital Ronell and raumlaborberlin

6 Thursday 23 April, 7.00pm

Iron Designer, organized in conjunction with Studio-X/Columbia GSAPP and DUMBO Improvement District

Iron Designer is organized by Mitchell Joachim, Ioanna Theocharopoulou and Gavin Browning, Columbia GSAPP, as a continuation of ECOGRAM: The Sustainability Question.

Featuring teams of M.Arch students from Columbia GSAPP, CCNY, Parsons and Pratt, IRON DESIGNER is a real-time, ecologically-oriented and challenge-based happening loosely based on “Iron Chef”.

Location: The Archway in DUMBO

7 Friday 24 April, 7.30pm

Screening of Gets Under the Skin Films and Videos on Modernist Architecture curated by Hajnalka Somogyi

Screening of Utopie 18, a movie by Raumlabor, followed by open discussion with the public.

Screenings will take place in the Spacebuster, located under the High Line at 508 W25 St at 10th Ave in Chelsea

8 Saturday 25 April

3pm Workshop

4.30pm Sandwiches by raumlaborberlin

5pm Poetry Slam

On Saturday, April 25th 2009, Storefront for Art and Architecture and Myrtle Avenue Brooklyn Partnership will organize a joint community-oriented event to be held in the unused space under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway along Park Avenue. The focus of this workshop will be on how disused spaces of this kind can be re-imagined as neighborhood assets. During activities facilitated by planners and designers including raumlaborberlin, workshop attendees will be able to share their thoughts by sketching, through discussions, and by exchanging ideas. The event will be free and open to the public. Location: Park Ave btw Washington Ave and Hall Street (under the BQE), Brooklyn

spacebuster from raumlaborberlin on Vimeo.

9 Sunday 26 April, 8.00pm

Finissage – closing reception and goodbye to Raumlabor (33 Flatbush Ave, Brooklyn)

The Spacebuster in NYC

Joseph Grima, NYC, May 2009

In his cameo appearance early on in the mythical 1984 movie Ghostbusters, the legendary Eyewitness News anchor Roger Grimsby solemnly announces on the airwaves: “Good morning, I’m Roger Grimsby. Today, the entire Eastern Seaboard is alive with talk of incidents of paranormal activity. Alleged ghost sightings and related supernatural occurances have been reported across the entire Tri-State area.” Quarter of a century later, paranormal activity appears to have subsided, but that’s not to say all is quiet, dull, business as usual in the streets, plazas and open spaces of New York City – at least not this April. The celebrated Ecto-1 Cadillac may be long gone, but the Spacebuster is here, and although the Ghostbusters may have retreated into early retirement, their architectural equivalent, Raumlabor, are busier than ever. For although ectoplasms have not been sighted in New York since 1989 – when Ghostbusters II was released – there is plenty of work here for anyone intent on engaging the ghostly abandonment of the city’s leftover spaces. And this is precisely what Raumlabor’s mission is.

The principle behind the Spacebuster is simple. Take an archetypal American step van (the kind used by DHL, UPS or the US Postal Service for deliveries). Attach a large, translucent, balloon-like sac to its rear entrance. Place a ramp leading down from the delivery van’s cab into the bubble, and beneath that a fan that constantly pumps air into the enclosure. LAy down a carpet on the floor, and switch on the fan. In a few minutes, a vehicle and a large balloon are joined in matrimony to become a mobile, self-powered, flexible and adaptable work of profoundly non-site-specific architecture.

But what is the point of all this? Let’s take a step back. Raumlabor hails from Berlin, a city in which space was traditionally abundant, and where money is less critical to innovation than intuition. In the ‘90s, Berlin was unexpectedly engulfed in a fireball of construction, comparable to what we have seen more recently in Dubai or Beijing; space, and particularly public space, was attacked with the weapons of speed and aggressive, regimented policy. It was party time for architects in Berlin, but only for the 60 to 80 year olds. As Niklas Maak puts it in the introduction to Acting in Public, a monographic book on Raumlabor’s recent work, the government policies of the time were “comparable to the pathological behaviour of parents who furnish their child’s first flat according to their own tastes – which is exactly what the centre of Berlin now looks like: dreary sandstone blocks”.

Cities are made up of buildings, but also of people; with the physical definition of Berlin’s new urban form beyond their reach, the younger generation voluntarily engaged the city’s social fabric, transforming this into their site of operations and area of influence. It was in this way that the Kitchen Monument, an inflatable structure that inspired the form of the Spacebuster, was born in 2006. Kitchen Monument, together with many of Raumlabor’s early projects, represented a new approach to urbanity, one centred on the behaviour of people rather than the arrangement of buildings. The Kitchen Monument’s seductive appearance was an ironic commentary on the smooth architectural forms architects dreamed of; at the same time it was a hospitable, womb-like space capable of transforming any one of the city’s many inhospitable, abandoned, left-over spaces into a gathering place, a temporary node of vitality; this it achieved through the simple guise of extracting the most intimate of domestic spaces, the kitchen, and placing it in public space. In a short period of time a flurry of sightings of the Kitchen Monument was recorded in squares, next to bridges, beneath flyovers, in parks and in construction sites around the city. People ate, drank, talked, danced and cooked – in public space. Yet most critics were not even sure if the object in question could even be called “architecture”.

As it turned out, the exquisite simplicity of the Kitchen Monument struck a nerve far beyond the confines of Berlin. Soon it was touring Europe, making appearances all across Germany, in Poland and in Liverpool. In 2008, Storefront for Art and Architecture invited Raumlabor to engage a very different environment from their home city of Berlin: the density of Manhattan and the complex social fabric of Brooklyn. In a city where space is one of the most valuable commodities – even just for one evening – mobility was crucial; thus, the Spacebuster was born. From 16 to 26 of April, for 10 consecutive evenings, New Yorkers held conversations, watched screenings, witnessed performances, dined, drank, talked and listened to music in car parks; under highways; beneath the High Line; in abandoned factories. The Spacebuster became a device for rediscovering and reappropriating the city, and experiencing it in collectively.

As Vito Acconci stated in a recent interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, “The thing that terrifies me about architecture is that by designing a space you are necessarily also designing the way in which people behave in that space”. One of the remarkable qualities of the Spacebuster (and the Kitchen Monument) is that by virtue of its humble, cheap construction it is born free from the shackles of authority to which “Architecture” is beholden by convention. Through the milky, semi-translucent skin of the Spacebuster’s bubble, many saw the city around them in sharper detail than they had ever seen it before.